- Home

- Timothy W. Ryback

Hitler's First Victims

Hitler's First Victims Read online

ALSO BY TIMOTHY W. RYBACK

Hitler’s Private Library: The Books That Shaped His Life

The Last Survivor: Legacies of Dachau

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright © 2014 by Timothy W. Ryback

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, Penguin Random House companies.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ryback, Timothy W., author.

Hitler’s first victims : the quest for justice / Timothy W. Ryback. —

First edition.

pages cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-385-35291-8 (hardcover)—ISBN 978-0-385-35292-5 (eBook)

1. Hartinger, Josef, 1883–1984. 2. Public prosecutors—Germany—Biography. 3. Nuremberg Trial of Major German War Criminals, Nuremberg, Germany, 1945–1946—Sources. 4. Special prosecutors—United States—History. 5. Governmental investigations—United States—History. 6. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945) 7. National socialism—Germany—History. I. Title.

KK185.H33R93 2014 341.6′90268—dc23 2013050971

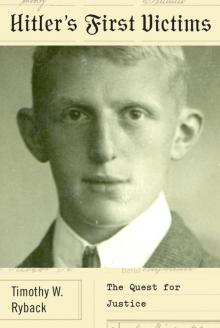

Jacket photograph: University of Munich Archives

Jacket design by Oliver Munday

v3.1_r2

IN MEMORY OF THE FIRST FOUR VICTIMS

OF THE HOLOCAUST

Rudolf Benario, age 24, d. April 12, 1933

Ernst Goldmann, age 24, d. April 12, 1933

Arthur Kahn, age 21, d. April 12, 1933

Erwin Kahn, age 32, d. April 16, 1933

How are such things possible in a country that was once so orderly, that once belonged to the leading cultural nations of our era and that, according to its constitution is a free, democratic republic?

E. J. GUMBEL, Four Years of Political Murder

CONTENTS

Cover

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Prelude to Justice

PART I Innocent

1 Crimes of the Spring

2 Late Afternoon News

3 Wintersberger

4 Witness to Atrocity

PART II … Until Proven …

5 The State of Bavaria

6 Rumors from the Würm Mill Woods

7 The Utility of Atrocity

8 Steinbrenner Unleashed

9 The Gumbel Report

10 Law and Disorder

11 A Realm unto Itself

12 Evidence of Evil

PART III Guilty

13 Presidential Powers

14 Death Sentence

15 Good-Faith Agreements

16 Rules of Law

Epilogue: The Hartinger Conviction

Appendix: The Hartinger Registers

Notes

Acknowledgments

Illustration Credits

A Note About the Author

Illustrations

Prelude to Justice

ON THE AFTERNOON OF Wednesday, December 19, 1945, shortly after the midday recess, Major Warren F. Farr, a Harvard-educated lawyer, took the podium before the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg to make a case for applying the dubious legal concept of collective guilt. The assistant trial counsel of the American prosecution team intended to prove, he told the tribunal, that the Schutzstaffel, Adolf Hitler’s black-uniformed “protection squads,” was a “criminal organization” and that its members should be held collectively responsible for the myriad atrocities perpetrated in its name.

“During the past weeks the Tribunal has heard evidence of the conspirators’ criminal program for aggressive war, for concentration camps, for the extermination of the Jews, for enslavement of foreign labor and illegal use of prisoners-of-war, for deportation and Germanization of conquered territories,” Major Farr crisply reprised. “Through all this evidence the name of the SS ran like a thread. Again and again”—throughout his discourse Farr jabbed the air with his pencil—“that organization and its components were referred to. It is my purpose to show why it performed a responsible role in every one of these criminal activities, why it was—and, indeed, had to be—a criminal organization.”

Farr spoke in a voice that was firm and resolute, but noticeably restrained, seeking to retain the solemnity with which Robert H. Jackson, chief prosecutor for the United States, had opened the prosecution four weeks earlier. “The wrongs which we seek to condemn and punish have been so calculated, so malignant, and so devastating,” Jackson had observed, “that civilization cannot tolerate their being ignored, because it cannot survive their being repeated.” Jackson enumerated a triad of transgressions—crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity—as the phalanx of twenty-one defendants watched from the dock. They seethed defiant indifference, belligerence, and arrogance. Former Luftwaffe chief Hermann Göring slouched in the corner beside Rudolf Hess. The statuesque Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg appeared in a three-piece suit, as did the Third Reich’s banker, Hjalmar Schacht. The military high command donned uniforms. Wilhelm Keitel blamed Hitler. “Hitler gave us orders—and we believed in him,” Keitel said. “Then he commits suicide and leaves us to bear the guilt.” Julius Streicher, the virulently anti-Semitic editor of Der Stürmer, blamed the Jews. Ernst Kaltenbrunner, the highest-ranking SS officer to stand trial at Nuremberg, objected to being forced “to serve as an ersatz for Himmler,” who had sidestepped justice with the snap of a cyanide capsule. Only Hans Frank, the former governor-general of occupied Poland—“a lawyer by profession, I say with shame,” Jackson noted—readily admitted to his own guilt and that of his country. After viewing film footage of the liberated concentration camps, Frank said to his fellow defendants, “May God have mercy on our souls.” He was equally contrite before the tribunal. “A thousand years will pass,” he would tell the court, “and the guilt of Germany will not be erased.” But Jackson knew that crime as well as punishment was on trial in Nuremberg. “We must never forget that the record on which we judge these defendants today,” he reminded the court, “is the record on which history will judge us tomorrow.”

Now, on the twenty-third day of the trial, as Farr prepared to leave his mark on judicial history, the courtroom solemnity that had greeted Jackson gave way to distraction. Farr’s fellow jurists shuffled papers. The defendants chatted among themselves or stared blankly into the distance. Göring planted his jowled face on the dock rail like a bored schoolboy. Frank, in dark glasses, sat in shaded, sinister silence. Previously, the tribunal president, Sir Geoffrey Lawrence, had grown noticeably impatient as Colonel Robert Storey, executive trial counsel, presented a meticulously researched case against the Nazi Sturmabteilung, the brownshirt SA storm troopers. Telford Taylor, Jackson’s deputy and eventual successor, recalled that the defendants had “roared with laughter” each time the tribunal president interrupted Storey. Now it was Farr’s turn. “Farr had his troubles with the tribunal,” Taylor remembered. “Its members were still nursing the irritation Storey had aroused and perhaps wanted to avoid giving the impression that he had been singled out for criticism.” In addition, Taylor noted, “it was the next-to-last day before the Christmas break, and everyone was tired and eager to get away.”

Farr forged into the courtroom fatigue. “About a week or ten days ago there appeared in a newspaper circulated in Nuremberg an account of a visit by that paper’s correspondent to a camp in which SS prisoners of war wer

e confined,” he said. “The thing that particularly struck the correspondent was the one question asked by the SS prisoners. Why are we charged as war criminals? What have we done except our normal duty?” It was his intention that afternoon, Farr informed Sir Geoffrey and his fellow judges, to answer that question with evidence that proved the SS was “the very essence of Nazism.” But as Farr began detailing the structure and nature of the SS, pointing his pencil toward the wall-size chart of this hydra-headed monster—the General SS, the Gestapo, the Security Department, the Death’s Head Unit, the Waffen SS—with SS Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler as its leader, Sir Geoffrey grew peevish. “Major Farr,” he said. “To go into this degree of detail about the organization of the SS?”

The American judge, Francis Biddle, joined the sniping. When Farr read a top-secret order from Hitler relating to the structure, membership, and responsibilities of the SS, dated August 17, 1938, then quoted a speech by Himmler from October 1943 in Poznan on the militarized SS police in the occupied territories and quoted an article by Himmler, Biddle intervened. “What has what you just read got to do with what you are presenting?” he asked irritably. Farr insisted on the need to establish the SS as a “criminal weapon” of the National Socialist regime. “Yes, but Major Farr, what you have to show is not the criminality of the people who used the weapon,” Sir Geoffrey objected, “but the criminality of the people who composed the weapon.”

Farr did not budge. “I quite agree I have to show that,” he said. “I suppose I have to show, before showing the persons involved knew of the criminal aims of the organization, what those criminal aims were.” This, Farr knew, was the core of his case. For the last twenty-three days, the prosecution had presented hundreds of pages of evidence, citations from speeches, directives, and top-secret memoranda. They had shown nightmare footage from the concentration camps. They had introduced as evidence tattooed flesh and a shrunken human head. “It is unnecessary to repeat the evidence of wholesale brutality, torture, and murder committed by SS guards,” Farr said. “They were not the sporadic crimes committed by irresponsible individuals but a part of a definite and calculated policy, a policy necessarily resulting from SS philosophy, a policy which was carried out from the initial creation of the camps.”

Farr cited verbatim and without apology a Himmler speech from 1942, Document 1919-PS, on the necessity of the concentration camps. “We shall be able to see after the war what a blessing it was for Germany that,” Farr quoted Himmler, “in spite of all the silly talk about humanitarianism, we imprisoned all this criminal sub-stratum of the German people in concentration camps. I’ll answer for that.” Farr paused. He looked to the defendants’ dock, from which Himmler was absent.

“But he is not here to answer,” Farr said. He turned to Sir Geoffrey. “Certainly there was no ‘silly humanitarianism’ in the manner in which SS men performed their tasks,” he told the British aristocrat. “Just an illustration,” he said. “I have four reports, relating to the deaths of four different inmates of the Concentration Camp Dachau between 16 and 27 May, 1933.” Farr held a sheaf of evidence collected in the spring of 1933 by the Munich prosecutor’s office. “Each report is signed by the Public Prosecutor of the District Court in Munich and is addressed to the Public Prosecutor of the Supreme Court in Munich. These four reports show that during that two-week period in 1933, at the time when the concentration camps had barely started, SS men had murdered—a different guard each time—an inmate of the camp.”

These were not manuals or speeches or directives or confidential memoranda. This was hard evidence, the stuff on which successful criminal prosecutions were built: signed depositions; police reports; crime scene sketches; forensic reports; autopsies; original black-and-white photographs of abused human bodies with lacerated backs and buttocks, cracked necks, and deeply gashed flesh with dangling sinews and glimpses of bone; and, most important, the names of the SS personnel indicted for these murders. This was “an illustration of the sort of thing that happened in the concentration camps at the earliest possible date, in 1933. I am prepared to offer those four reports in evidence and to quote from them”—and here Farr paused to observe acidly—“if the Tribunal thinks that the point is not too insignificant.”

“Where are they?” Sir Geoffrey asked.

“I have them here,” Farr said. “I will offer them in evidence. The first is our Document 641-PS.”

THE DOCUMENTS THAT Farr offered Sir Geoffrey on that late December afternoon contain some of the earliest forensic evidence of the systematic execution of Jews by the Nazis. While these initial Dachau killings do not represent the homicidal process in its full horrific scope, the murder of Jewish detainees in Dachau that spring involved the constituent parts of the genocidal process—intentionality, chain of command, selection, execution—we have come to know as the Holocaust.

I first became aware of the Dachau murders while on assignment as a “far-flung correspondent” for The New Yorker in the early 1990s. At the time, Hans-Günter Richardi had already detailed the killings in his superb account of the early Dachau Concentration Camp, Schule der Gewalt (School of Violence), as had Prof. Dr. Lothar Gruchmann in his fascinating though daunting twelve-hundred-page compendium, Justiz im Dritten Reich (Justice in the Third Reich). I felt there was little left to add.

Later, I discovered in a Munich archive the unpublished, and seemingly forgotten, account of these incidents by Josef Hartinger, the Bavarian deputy state prosecutor who had collected the forensic evidence that Farr was to present in Nuremberg twelve and a half years later. In two extended letters, one dated January 16, 1984, and the other dated February 11, 1984, Hartinger, ninety years old at the time, revealed an astonishingly bold plan to have the camp commandant, Hilmar Wäckerle, arrested on murder charges, and the SS guard units evicted from the concentration camp system.

At the time, Hartinger was a thirty-nine-year-old Munich prosecutor and a rising star in the state civil service. Like many that spring, he sensed the horrific nature of the Hitler regime, but like few others, he recognized its fissures and early fragility, and like fewer still, he willingly risked everything—his career, his welfare, even his life—in the unflinching pursuit of justice. While Hartinger’s fight for accountability couldn’t stem the tide of Nazi atrocity, his story suggests how vastly different history might have been had more Germans acted with equal courage and conviction in that time of collective human failure.

PART I

INNOCENT

1

Crimes of the Spring

THURSDAY MORNING OF Easter Week 1933, April 13, saw clearing skies that held much promise for the upcoming holiday weekend. Mild temperatures were foreseen for Bavaria as they were throughout southern Germany, with a few rain showers predicted for Friday, but brilliant, sunny skies for the Easter weekend. Previous generations hailed such days as Kaiserwetter, weather fit for a kaiser, a playful gibe at the former monarch’s father, who appeared en plein air only when sufficient sunlight permitted his presence to be recorded by photographers. In the spring of 1933, some now spoke in higher-spirited and more reverential tones of Führerwetter. It was Adolf Hitler’s first spring as chancellor.

Shortly after nine o’clock that morning, Josef Hartinger was in his second-floor office at Prielmayrstrasse 5, just off Karlsplatz in central Munich, when he received a call informing him that four men had been shot in a failed escape attempt from a recently erected detention facility for political prisoners in the moorlands near the town of Dachau. As deputy prosecutor for one of Bavaria’s largest jurisdictions—Munich II—Hartinger was responsible for investigating potential crimes in a sprawling sweep of countryside outside Munich’s urban periphery. “My responsibilities included, along with the district courts in Garmisch and Dachau, all juvenile and major financial criminal matters for the entire jurisdiction, as well as all the so-called political crimes. Thus, for the Dachau camp, I had dual responsibilities,” he later wrote.

Deputy Prosecutor Hartinger

was a model Bavarian civil servant. He was conservative in his faith and politics, a devout Roman Catholic and a registered member of the Bavarian People’s Party, the centrist “people’s party” of the Free State of Bavaria, founded by Dr. Heinrich Held, a fellow jurist and a fierce advocate of Bavarian autonomy. In April 1933, Hartinger was thirty-nine years old and belonged to the first generation of state prosecutors trained in the processes and values of a democratic republic. He pursued communists and National Socialists with equal vigor, and since Hitler’s appointment as chancellor had watched the ensuing chaos and abuses with the confidence that such a government could not long endure. The Reich president, Paul von Hindenburg, had dismissed three chancellors in the past ten months: Heinrich Brüning in May, Franz von Papen in November, and Kurt von Schleicher just that past January. There was nothing preventing Hindenburg from doing the same with his latest chancellor Adolf Hitler.

Until then, Hartinger’s daily commerce in crime involved burned barns, a petty larceny, an occasional assault, and, based on the remnant entries in the departmental case register, all too frequent incidents of adult transgressions against minors. Forty-one-year-old Max Lackner, for example, was institutionalized for two years for “sexual abuse of children under fourteen.” Ilya Malic, a salesman from Yugoslavia, was arrested after he “forced a fourteen-year-old to French-kiss.” Hartinger spoke discreetly of “juvenile matters.” Homicides were rare. The only registered murder for those years was a crime of passion committed by forty-seven-year-old Alfons Graf, who put four bullets into the head of his companion, Frau Reitinger, when he discovered her in the back of his company car with another man.

But that year, following Hitler’s January appointment as chancellor and the dramatic arson attack a month later that saw the stately Berlin Reichstag consumed in a nightmare conflagration of crashing glass, twisted steel, and surging flames, the jurisdiction was swept by an unprecedented wave of arrests in the name of national security. In Untergrünberg, the farmer Franz Sales Mendler was arrested for making disparaging remarks about the new government. Maria Strohle, the wife of a power plant owner in Hergensweiler, told a neighbor that she heard Hitler had paid 50,000 reichsmarks to stage the arson attack on the Reichstag; she was sentenced to three months in prison, as was Franz Schliersmaier in Bösenreutin, who put the amount at 500,000. One Bavarian was indicted for comparing Hitler to Stalin, and another for calling him a homosexual, and still another for suggesting he did not “look” German. “Hitler is a foreigner who smuggled himself into the country,” Julie Kolmeder said at a Munich beer garden a few streets from Hartinger’s office. “Just look at his face.” A Munich coachman crossed the law with the indelicate aside, “Hitler kann mich im Arsch lecken.” Euphemistically: Hitler can kiss my ass. More than one person was prosecuted for calling a Nazi a “Bazi.”*1 Thousands of others were taken into Schutzhaft, or protective custody, for no apparent reason at all.

Hitler's Private Library

Hitler's Private Library Hitler's First Victims

Hitler's First Victims